MP Hopkins

April 2024

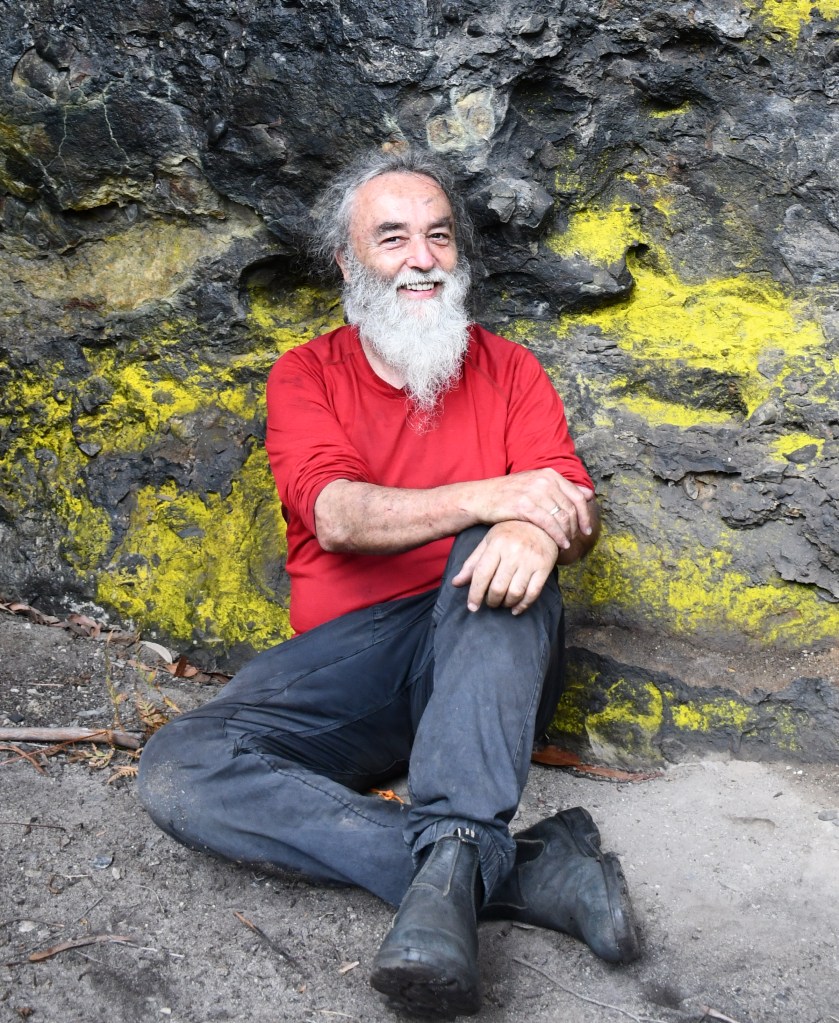

Photo: Adam Gottlieb of Jim Denley at Hidden Valley.

MH: I wanted to talk about the storm track [Storm:RB] on With Weather Volume 2: Gadigal Country. You describe the vinyl material protecting the microphones acting like a skin or a membrane for the mics. I like how you talk about the raindrops becoming like percussionists as they fall on this material.

JD: It was literally a storm and it had started raining and I’m thinking, well, I better protect the microphones. So, I put these vinyl cases that I’ve got over the top of the machines and I tried to prop them up so they didn’t stop the microphones from transducing and inscribing worlding. I didn’t want to wrap them up. The storm’s happening and it’s sounding amazing, and I really want to record this. So, I bunged these two vinyl cases over the top of the two hard disc recorders without thinking about it too much and just started playing. When I got back home and listened to the recordings, I realised that those vinyl wallets above the microphones were incredibly proximate to the raindrops. The raindrops weren’t that heavy, so you get that sound of rain hitting vinyl, which we all know because we go out in the rain with an umbrella or hoodie raincoat on. We all know that thing; it’s incredibly spatial because it’s very proximate to our ears. It’s like extreme stereo.

MH: This makes me think about your ideas of the musickin and co-creation with non-humans and the elements. You’ve been playing this way for a long time, and I imagine you’re really familiar with certain sounds of say, water and wind and trees, but I was wondering if, once you’ve made a recording and you’re listening back, are there many sounds that seem ambiguous to you?

JD: I think I’ve thought about that quite a bit and I think I’ve come to the realisation that everything is unanticipatable. I guess that’s indeterminacy, and if one takes that really seriously, unanticipatable seems to be a word that describes the surprise of that. But the unanticipatable can be the known. I know that such and such a car is coming up the street, but if I’m going to be really attentive to the sound, you can never know exactly what the realisation of that performance is going to be – it could be a late 60s Datsun or a Tesla. So often we just identify, and it’s coded, and we read the code. There’s David Rothenburg, the clarinettist, who says we don’t really listen to things that we know. And so as soon as we can name it, we kind of don’t listen anymore. And I think that’s partly true, but I don’t think it has to be true. Once something’s identified and it’s named, you know it, but you don’t know its becoming. You don’t know each iterative creation of that thing. Because each moment is highly specific, the acoustics are different, the things around are different.

MH: Right, but it seems that certain sounds in certain contexts take on a bit of a different agency. Sometimes they act in a way we know, but sometimes they’re doing something unfamiliar. They can emerge and kind of linger in an uncertain way. I was thinking about this when I was listening to As Weather Volume 3: Budawang Mountains, in relation to the diffraction pieces [Diffraction Study #1 and Diffraction Study #2]. There’s something about movement in these; about the sound not moving in a straightforward or predictable way. You’ve been playing in the Budawangs for a long time, and I’m sure there are familiar sounds to you there, familiar acoustics, but the sound of you and the place becomes blurred in an unusual way for me. There’s this incredible thing happening with distance and perspective in those studies. Certain sounds are made, but if they’re distant or up close, moving away or getting closer; this all becomes very ambiguous at times.

JD: Well those two studies are from different days, which are a whole different worldings. It’s the same place. I’m the same – well, I’m seemingly the same flute player [laughs] – playing what I can play, what I’ve learned to play at that point in my individuating. So, you wouldn’t expect there to be too much variation. But they’re completely different time spaces. And I’m different each time because the weather is different on the two days. One recording is a very calm day where there’s not much wind around, and then the next day was a lot windier, more overcast. I remember the first day as this very beautiful sunny day – in the middle of the day – and because it’s a ravine it’s only in the middle of the day that you get direct sunlight. The sunlight hitting the creek in the middle of the day was just incredibly beautiful. And the next day didn’t have that thing because it was overcast, and it was windy and cold. So, one tends to think of that as being the same place but if you’re going to really embrace indeterminacy, or unanticipatability, it’s not the same place, you know? I’m not the same person. It’s the next day, I’ve had a night in a cave [laughs], I’ve had some sort of weird breakfast, things are different.

MH: What sort of breakfast do you have when you’re out there? [both laugh]

JD: Sometimes I make these little damper cakes. Just like flour and water. Fry them up in a little bit of olive oil. And they’re good. I remember going out there with Aviva, Adam and Victoria for the first volume [In Weather Volume 1: The Hidden Valley]. We all ended up at the Hidden Valley. And I remember making these super simple cakes, just like flour and water, fried in a little billy tin lid. And then all we had was a bit of tahini and dried apricots to put in the middle. They were so delicious [laughs]. I think it’s often when you’re in those situations that the simplest stuff just tastes amazing. But it’s a bit like that with the sound as well because you’ve gone so far away from Nowra, or the main highway.

MH: So, the first and third volumes are both in and around the Budawang Mountains, on Yuin country. How long have you been going there to play?

JD: I guess, like 30 plus years [pause] The vegetation there is incredibly mutable. There’s nothing fixed about that. It’s always in a state of flux and changing. And I guess the musicking that I’m interested in is all about that flux, or nothing being fixed. Nothing being solid. I mean, sometimes it doesn’t work. I’ll listen back to recordings. And I go, no, that’s not what I’m aiming at. Because I guess one is stuck with one’s style a bit. Or the things that one knows about, especially with instrumentalism. It’s hard to move away from certain fixities, certain things that you know to do.

MH: With this idea of musicking in that space, after going there for 30 years, I’m wondering about that timescale in relation to the fixity of what you’re playing. Have there been moments where there’s been a really radical shift in what you’re playing? Have there been any points over the years where you’ve noticed that you started playing in a really different way?

JD: Interesting question. I think the way of answering it could be to take this emphasis on me – or this fixed self – away. So that if I’m doing what I’m aiming to do, and what I think is possible, there is no sort of fixed self, which has fixed ways of doing things. When I listen back to recordings and I think they don’t work, I’ve just gone into a habitual, fixed state. When it works for me is when that interest in the self, or anything being defined dissolves. The fly that goes past the microphone really closely can be the main voice. Or a distant bird that happens to go into a cycle of doing its thing, or the wind coming out of the valley. They’re equal actants; equal musickin. The music, which is the overall thing that I’m interested in, is not about individual sounds – not about that fly, or this flute player, or this rock, or this tree – it’s about the polyphony and the relationality. The combinatoriality of how all those things work together, and if they make a certain poetry together. The poiesis of the interaction between them all creates something special. And in that moment, I might just be playing the most boring thing I’ve ever played. But if it’s working well in relationship to everything and creating this thing – which is novel, which is not my playing or the sound of the wind in the trees – it’s the relationship between all those things. I think one often gets confused because one listens in to the flute, or the bird. And in the end, I don’t think that’s what’s interesting.

MH: That makes a lot of sense, because in me asking if you’re going in with this intention to play something new, that seems to void the whole idea of musicking in that space with the musickin you’re playing with. I suppose it’s pointless to go in wanting to do anything in particular. The relationship being about all the sounds is interesting, because it is when they kind of fuse together that it creates that beautiful ambiguity that we talked about earlier in relation to the diffraction studies.

JD: I think in the one on the calm day, study number one, I remember being with ravine and thinking some of those distant bird calls are so high pitched. And then I was interested in this whistle tone that I was creating on the flute where you have a lower fundamental tone and then there are all these other super high frequency tones that are created by the flute embouchure. And even I can’t tell sometimes when I’m listening back to it now, which are the birds in that high frequency range and which are the bits of flute.

MH: Totally, I think that’s what I was trying to describe before – I can’t tell which sound is which. For me, this is why thinking about perspective and distance are really interesting in this work because the distances between you and everything else get lost. It’s hard to know which direction the sounds are moving, if they’re coming or going, if it’s you or a bird.

JD: I guess there’s that idea about acoustics too. We often think of acoustics in echo terms. And especially when it comes to concert halls and walled rooms, and chambers [pause] reverberant spaces. And this ravine has something of that room like quality. Being a ravine, it has a deep cut in the rock from the water and the elements cutting the ravine over time, over aeons. So, you have something of a chamber like quality to the acoustic, but there’s so many trees there as well because there’s rainforest. The walls of that chamber are never square or geometric, the way rooms are. I guess a lot of concert halls try and mimic these sorts of acoustics because they try and put in all sorts of surfaces that aren’t simply reflective. And I’ve often thought about this, especially when I’m in the Budawangs. I’m in these spaces which are quite reverberant in the way we think of concert halls, but there are so many other surfaces in between. Trees, basically, which make a very complicated and multiplicitous acoustic. So, diffraction or interference [pause] I don’t get back a clear echo or resonance; things are read through other things.

MH: Diffraction, refraction, reflections, [pause] all this different movement. With the different volumes being in, as, and with weather – they are all different types of engagements with how the weather is changing the space.

JD: That was actually a mistake [laughs]. As part of my PhD research, I thought at first, I was doing in weather, and I was pretty pleased with myself. And then the more I thought about that, I went, in? Is that the right way of describing it? And then I started thinking, well, it’s much cooler if we go, it’s with.

MH: Well, that fits more with the musickin idea; a way of co-creating with the other things.

JD: Yeah, and after a while I sort of went, hang on, it’s much more profound to sort of go as. Humanity, of course, is weather. There’s this guy, Nick Lane, he talks about dissipative structures in weather – like storms – and that they dissipate energies out. At one stage, halfway through the book [The Vital Question] he says human beings can be thought of as dissipative structures, like energies, a way of congealing energy into sort of a vitality for a period, from birth to death. And then there’s this entropic sort of dissipation. But for a time, we bring these energies together into a vitality, which we call life. And so, he says human beings can be seen as weather; as dissipative structures within weather. And so that tree out the window there, it’s not in weather, it’s not even with weather – it is weather. And presumably, that’s what scientists have been saying – screaming at us – for the last 40 years. That we’re not in, or even with; we are the weather, because we are reconfiguring it.

Photo: Jim Denley of Hard Disk Recorder at Trumper Park.